There are many animals that seem unassuming, but are vitally important to the health of our ecosystems. A perfect example of this is the horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus). They do many important things in our beaches and bays, including mix up sediment and add oxygen back into the mudflats. Similarly, their eggs are a crucial food source for migrating shorebirds like red knots and ruddy turnstones. They are also very important to humans, for a compound in their blood used to test for bacterial contamination, for bait in the eel, conch, and whelk fisheries, and for vision research.

Every spring in May and June during the full and new moons, horseshoe crabs move shoreward to reproduce on our local beaches. Over the past few decades, horseshoe crab populations have been declining. This is attributed to a combination of overharvesting and a loss of coastal habitat. To monitor their populations and provide critical information to those who regulate their harvest, spawning surveys have been used to determine if current regulations that are aimed to protect crabs are helping to at least maintain or increase the number of crabs. Sara Grady of the Massachusetts Bays Program South Shore (housed at the NSRWA) has been working with Mass. Division of Marine Fisheries to conduct horseshoe crab spawning surveys for eight years in Duxbury Bay, one of only a few sites that have been monitored consistently in Massachusetts.

To supplement the information from the spawning surveys, Grady (with the help of our citizen science volunteers) started tagging horseshoe crabs with small white plastic discs that are affixed to the crabs shell. Tagging began in Duxbury Bay in 2012 in cooperation with US Fish and Wildlife Service. The point in tagging them is to track whether crabs in the bay stay local or travel elsewhere and helps managers determine whether horseshoe crabs should be managed on a local or regional scale.The tags are simply numbered labels, so the data relies on reports by beachcombers and others who find the crabs and report them to the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

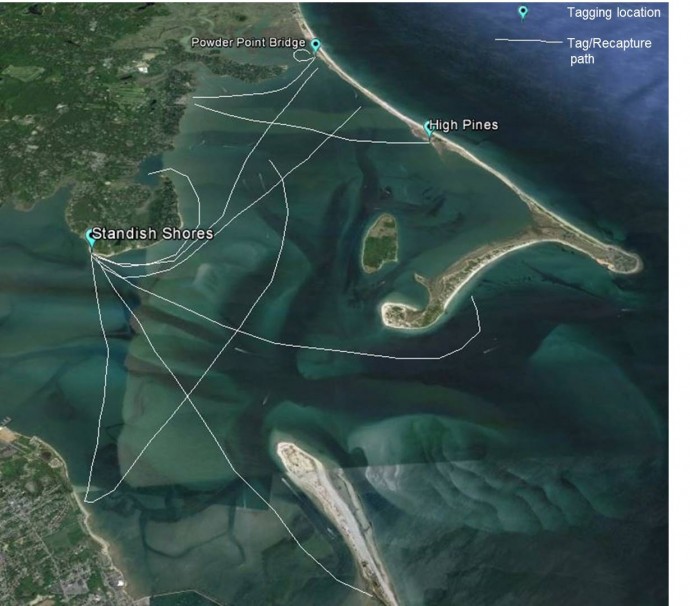

In the initial years of tagging (2012-2013), 100 crabs were tagged at High Pines and Powder Point Bridge along the eastern edge of Duxbury Bay. In the next round of tagging (2015), 250 crabs were tagged at Standish Shores and Powder Point Bridge. Sightings from beachcombers were recently compiled, and only 4 of the 100 crabs tagged in 2012 and 2013 were seen again. Similarly, of the 250 crabs tagged in 2015, only 8 were seen again. All the crabs that were found had stayed within the bay complex (see map).

So if you’re walking the beaches this spring and see a horseshoe crab with a tag on it, make sure to record the number and report it to the US Fish and Wildlife Service. We are relying on YOU to encounter these amazing creatures and help us determine where these animals go and how their populations are surviving.

To volunteer to help with this year’s Horseshoe Crab surveys, please fill out this form!