Owned By: (Private)

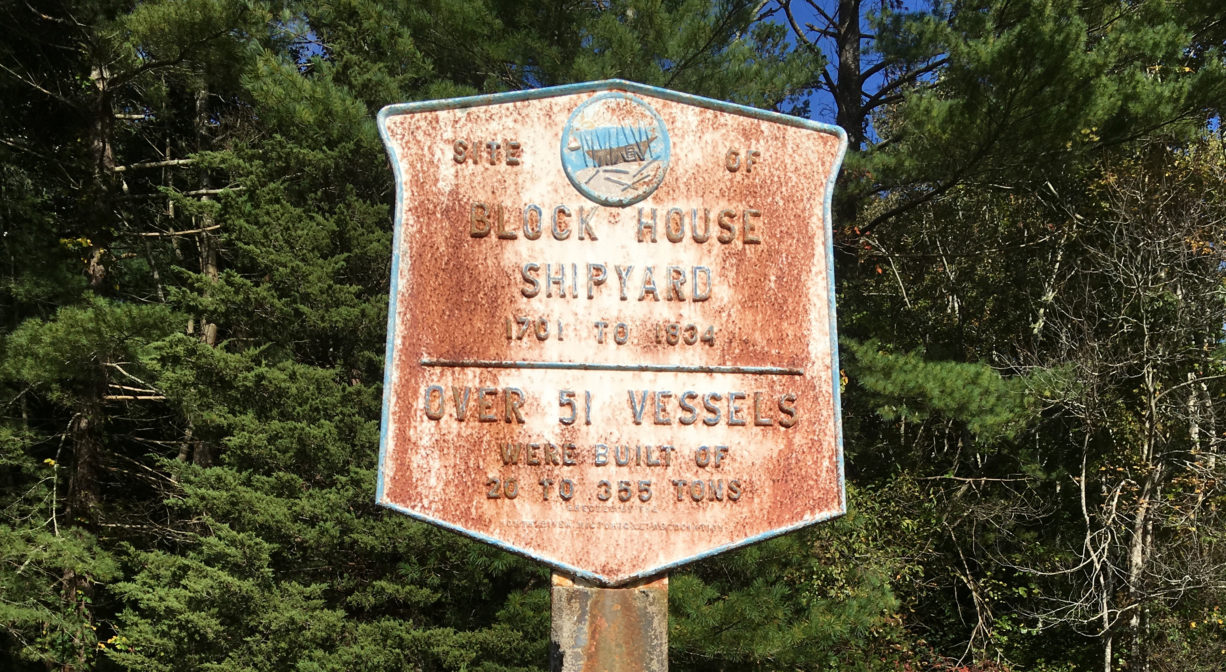

This shipyard, which was active from 1701 to 1848, is named for the building that was used as a garrison house, or “block house” during King Philip’s War. It was located at the elbow, just above The Rapids on the North River. A plaque marks the shipyard site. This is a historic site, with no public access, but you can see the site obliquely from the boathouse at the Norris Reservation. You can also view it from the water.

Features

William James was probably the first shipbuilder here (c. 1701), followed by his son, also William. Jotham Tilden later partnered with James to build ships here. His brother Luther Tilden was also involved. James, George and David Torrey followed in 1806.

This land is within the region of the Massachusett (or Massachuseuk) Native American tribe. For thousands of years, the land that today is known as Norwell was inhabited by indigenous people who grew crops, foraged, hunted, and fished in the Assinippi and North River areas. Circa 1617, a major outbreak of disease decimated an estimated 90% of the native population in New England, including the Massachusett and Wampanoag tribes that inhabited the South Shore. There are still descendants of these original inhabitants living here today. They are known as the Mattakeesett Tribe of the Massachusett Indian Nation , the Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag, and the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe.

When the Europeans first came to the South Shore in the 1620s, the local Native American tribes had just endured a plague of smallpox. Their populations were low. Also they did not conceive of land rights the same way that the Europeans did. So even though there are deeds signing over the rights to a lot of land to the colonists, it is likely that the native tribes thought they were giving the colonists the rights to use the land, not to own it exclusively.

By the 1670s, the native tribes had repopulated. Noting how the colonists were trying to drive them away, Chief Metacomet of the Wampanoag, aka King Philip, a son of Massasoit, began uniting local tribes to fight back. The Narragansetts, led by their sachem, Canonchet, initially tried to remain neutral, but they were involved in raids and skirmishes, and ended up being considered the enemy by the colonists. And so, King Philip’s War occurred . . . a three-year battle between the European Colonists and the native tribes.

A Colonial army was assembled – 1,000 militia men and 150 native allies. 27 men from Scituate joined the militia, to meet the colony quota of 158 men. Led by Governor Josiah Winslow and General James Cudworth, they attacked the Narragansetts in November 1675, burning villages throughout Rhode Island. The tribes fought back, burning towns such as Providence. More than half of New England’s towns were attacked. Twelve towns in the Plymouth and Rhode Island colonies were destroyed, with many more damaged. The colonial economy was nearly ruined, and one-tenth of the men eligible for military service (age 16-60) were killed. Ultimately the colonists prevailed, and the Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes were nearly destroyed.

Here’s how it played out locally: King Philip had made raids on Weymouth, Middleborough, and Bridgewater. Because of this, in Scituate, a watch with “fixed armes and suitable ammunition” had been set up with the youths and older men who remained in town. Additional militia were ordered up, and so 50 more Scituate men went off to fight.

There was a garrison at the home of Joseph Barstow in Hanover Four Corners with a guard of 10-12 men. Another garrison was established at Little’s Bridge (Route 3A) on the North River, and a third one at the home of John Williams, what became the Barker farm, near Scituate Harbor.

On May 19th 1676, the Native Americans began their attack in Hingham, burning 5 houses. They proceeded the next day into Norwell & Hanover. They knew that all of Scituate’s men were away, fighting the war closer to Rhode Island. They began at what is now Hanover Four Corners, burned the house of Joseph Sylvester, and also Robert Stetson’s sawmill on Third Herring Brook. While avoiding the garrison at Four Corners, they continued east, burning homes, killing cattle, destroying newly planted fields, and ultimately ruining 13 houses, a sawmill, and probably 10 barns. They did not succeed in taking the block house near Union Bridge (the site of Block House Yard), but they continued to the fort the Stockbridge Mill in Scituate. There was stockade located there, with Old Oaken Bucket Pond behind it. They fought all day. The Englishmen were led by Robert Stetson (age 64 at the time) and Isaac Chittenden (who was later killed in the fight). In the end, the colonists drove the native tribes away.

Another call for troops came soon after, for 25 men from Scituate. Somehow the quota was furnished, but it’s unclear how. King Philip was killed at Mount Hope in August 1676, which essentially ended the war, although a treaty followed in April 1678.

Habitats and Wildlife

Reverend William P. Tilden, whose father and uncle operated Block House Yard in the 1700s, wrote this description of the terrain. “The Block-house Yard was not well adapted to building. The ground was mostly springy and wet; the way to it was through a rocky pasture, with only a cart path, where deep ruts and frequent stones tried the heavy wheels, loaded with timber, and the necks of the patient oxen, which bore the swinging white oak trunks, planks, and knees. Then, when the timber was in the yard, there was not sufficient room for it. Beside this, when the vessel was launched, she had to run directly across the river into the mud on the other side. . . . Still, there were many vessels built at this yard.”

According to Joseph Foster Merritt (c. 1928), “A never failing spring of water gushes out of a fissure in a granite ledge on the place.” In season, this section of the river can be a good spot to catch striped bass. The forest surrounding this site is all second growth. All of the original trees were cut down and used to build ships.

This property is located directly on the North River. The North River rises from marshes and springs in Weymouth, Rockland and Hanson. It is approximately 10 miles in length, with its source at the confluence of the Indian Head River (Hanover) and Herring Brook (Pembroke). From there it flows through the towns of Hanover, Pembroke, Marshfield, Norwell, and Scituate to the Atlantic Ocean between Third and Fourth Cliffs, draining approximately 59,000 acres along the way.

Historic Site: Yes

Park: No

Beach: No

Boat Launch: No

Lifeguards: No

Hours: Dawn to Dusk

Parking: Water access only. No public parking or access.

Dogs: No

Boat Ramp: No

ADA Access: No

Scenic Views: Yes

Waterbody/Watershed: North River