Town of Pembroke: (781) 293-4674

Owned By: Town of Pembroke

The Pembroke side of Ludden’s Ford Park is 34 acres of open meadow and forested upland on West Elm Street, on the banks of the Indian Head River. It was known in the past as Luddam’s Ford Park. The Clapp Rubber Works (founded in 1873), the largest of its kind in the country, once stood here, on both sides of the river. Look for remains of the factory in the woods on the Pembroke side, just south of the walking trail.

The dam on the Indian Head River fueled this factory, as well as earlier mills and an anchor forge. Now it forces migrating fish to scale a fish ladder as they swim upstream to spawn. The pond created by the dam welcomes non-motorized boats and catch-and-release fishing. Due to mercury contamination from 19th and 20th century industries upstream, fish caught here may not be consumed. When boating, be careful to stay away from the dam.

There are informal launch areas for canoe, kayaks and small boats on both sides of the river. The property also features a picnic/passive recreation area.

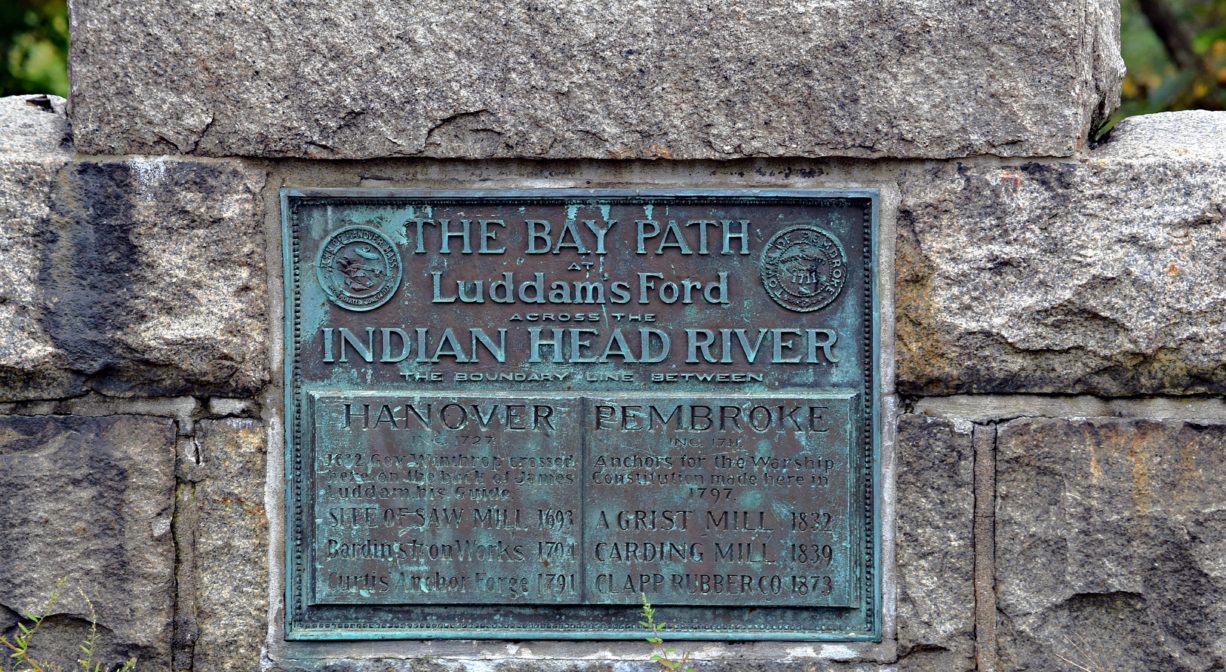

Walk across the bridge on West Elm Street to access the Hanover portion of Ludden’s Ford Park. Look for a historic marker at the center of the bridge, which was completed in 1894. Ludden’s Ford Park (Pembroke) also provides access to the trails of the 78-acre Tucker Preserve, owned by the Wildlands Trust.

FISHING ADVISORY: It’s important to know that some of our freshwater fisheries are contaminated with mercury, PFAS and/or other concerning substances. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health maintains an online database with up-to-date advisories regarding fish consumption, sorted by location. We recommend you consult this valuable resource when planning a fishing excursion.

Features

On the historic Old Bay Path from Plymouth to Boston, Ludden’s Ford (formerly known as Luddam’s Ford) is named for James Ludden, the guide who in 1632 carried Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Bay Colony across the river to visit Governor William Bradford of Plymouth Colony. Ludden was a settler, landowner and planter in the Wessagusset Colony at Weymouth.

In 1704, Thomas Bardin built a dam just above Ludden’s Ford, on the Hanover side. He also erected an anchor forge, which supplied the shipyards below. Around the same time, a bridge was built here.

Next at this site was the E. H. Clapp Rubber Works. In 1871, Eugene H. Clapp, a native of South Scituate (Norwell), invented a method for removing the fiber from old rubber and preparing it so it could be used again for new goods. He opened a reclaimed rubber manufacturing plant in Roxbury with two machines and two workers. In 1873 he purchased the George Curtis Anchor Works and moved his company to Hanover, where there were better water power facilities. Not having much capital, he and his cousin Fred Clapp made the minimum number of modifications to get the rubber mill up and running. Within a few days, the flumes were washed away by a flood, so they had to build new ones and also put in a new water wheel.

At first, water power was adequate to run the rubber works. It began with 2 grinding machines, but expanded quickly. Soon it could grind 1000 pounds a day. The mill was originally one story, but it increased to three. In 1879, steam power was added, which made the business grow so rapidly that they operated the factory day & night. In 1881, the building was destroyed by fire, and then within a month’s time, rebuilt on a much larger scale, with the best equipment available.

In 1886 Clapp built another mill, here on the Pembroke side of the river. By 1889, the mills employed 75-100 men – mostly locals — and could grind 20 tons per day, 40x more than when it started. According to the Briggs History of Shipbuilding in 1889, “(Clapp) has now complete accommodation for handling and utilizing all kinds of rubber material according to the latest and best known processes, both mechanical and chemical, is doing two or three times as much work as any of his competitors, and is handling more than one half of this business in the United States.” Today, Ludden’s Ford Park is serene and naturally beautiful. It is hard to imagine that only 150 years ago, the area was a booming industrial complex!

This land is within the region of the Massachusett (or Massachuseuk) Native American tribe. The Mattakeeset band of the Massachusett lived for thousands of years in the North River watershed. Their village included most of today’s Pembroke and Hanson. To learn more about local Native American tribes, we encourage you to interact with their members. The Massachusett tribe at Ponkapoag and the Mattakeeset band of the Massachusett share information on their websites.

Trail Description

From the parking area on West Elm Street, the main trail leads across a grassy meadow, with excellent views of the fish ladder and the Indian Head River. After entering the forest, the trail continues along the riverbank until it reaches a small stream. A bridge leads across the stream into the Tucker Preserve.

The Tucker Preserve offers several intersecting loop trails, some with gorgeous views of the Indian Head River. Beyond the boundaries of the Tucker Preserve are additional trails through the river valley, both in Pembroke and Hanson.

Ambitious hikers could explore more than 4 miles of trail here. Setting off from Ludden’s Ford in Pembroke, continue through the Tucker Preserve, and then follow additional trails through the woods and along the river. This will bring you to Rocky Run Conservation Area in Hanson. Cross the Indian Head River via the bridge on State/Cross Street, round the bend turning right toward Water Street, and then pick up the Indian Head River Trails on the Hanover side. Woodland trails and an old railroad bed follow the course of the river all the way to Ludden’s Ford Park in Hanover.

Across the street from the Hanover section of Ludden’s Ford Park, look for the Mattakeeset Trail, which extends for about a quarter mile, parallel to Indian Head Drive, within view of the river, and connects with the Chapman’s Landing and Iron Mine Brook Trails, adjacent to the Hanover Public Launch.

Habitats and Wildlife

The Indian Head River flows east through Ludden’s Ford Park and into the North River. It rises from the Drinkwater River and Factory Pond in West Hanover, and forms the boundary between Hanover and Hanson. It merges with Pembroke’s Herring Brook a short distance downstream of Ludden’s Ford Park, to form the North River at a spot called The Crotch. The North River flows 12 miles through Pembroke, Hanover, Norwell, Marshfield and Scituate, eventually making its way to Massachusetts Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

The Indian Head is freshwater and attracts many different species of animals to its banks and surrounding forest. Mass Wildlife stocks the river with brown and Eastern Brook trout. Herring and shad can be seen at the base of the fish ladder in the spring. These fish attract mammals such as raccoons, striped skunks, coyotes, minks, muskrats, osprey, and fox. The meadow is excellent habitat for dragonflies.

FISHING ADVISORY: The Indian Head River (IHR) has long been a popular fishing destination, and for good reason. The calm waters, miles of shoreline, and variety of fish make it an ideal location for the freshwater angler. Historically, this was a prime spot for herring, shad, smelt, bass, white and red perch, pickerel, horn pout, and even salmon. Due to mercury contamination from the National Fireworks site at Factory Pond in Hanover, the Massachusetts Department of Health has issued a health advisory that the general public should not eat any fish caught from Drinkwater River, Indian Head River or North River. While the source of the mercury contamination is located upstream, mercury bioaccumulates through the food chain, resulting in animals with increasingly higher concentrations of mercury in their bodies. Check current regulations prior to fishing in the IHR.

FISH MIGRATION: The fish ladder was constructed here with the intention of assisting migratory fish over the dam. Sadly, it is not very effective. Some fish do manage to get over it, though! In April and May, you can sometimes view herring here as they wait to enter the fish ladder. Look downstream of the dam at the right moment, and you might see thousands of fish. Unfortunately, due to the location of this fish ladder, in the middle of the spillway, we can’t figure a safe way to monitor or maintain the fish as they pass here. Thus we have no idea what their success rate might be, in getting past this dam. There is another dam — well, really just the rock remnants of one — just downstream of the State Street and Cross Street bridge in Hanson and Hanover.

We do know that the Indian Head River is a potential jewel in the crown of herring runs with restoration potential. We have been in initial discussions with the towns of Pembroke and Hanover about the feasibility of removing this dam. Stay tuned!

Diadromous fish spend one portion of their lives in saltwater and another portion in freshwater. These fish can be split into two categories: Anadromous and Catadromous. Anadromous fish spend the majority of their life in saltwater and return to freshwater to spawn. Catadromous fish spend the majority of their life in freshwater and return to saltwater to spawn.

Although anadromous and catadromous fish live opposite life cycles, they share the common need of freshwater rivers to survive. Unfortunately, habitat loss caused by dams and other human impacts like overfishing and pollution threaten the survival of these species. The protection of rivers like the Indian Head River is critical in providing safe breeding grounds and ensuring the continuation of the local species that rely on them.

Alewife – Alosa pseudopharengus: Also known as river herring, alewife are anadromous and are considered a keystone species. A variety of other fish, like striped bass, and wildlife prey on alewife to survive. Juvenile alewives consume algae, insect eggs and larvae, making them an important role in freshwater ecosystems. Due to dwindling populations, it is prohibited to harvest alewife both recreationally and commercially in Massachusetts.

American Eel – Anguilla rostrata: Despite their slender snake-like appearance, American eels are true fish with scales. The American eel is the only catadromous fish in North America and when mature, migrates out to the Sargasso Sea near Bermuda to spawn and then die. Like other fish species that rely on freshwater rivers for survival, the fragmentation of rivers due to dams, overfishing, water withdrawals and pollution continue to threaten eel populations.

Blueback Herring – Alosa aestivalis: Blueback herring, named for the visible bluish coloration near its dorsal fin, can be found along the Atlantic coast from Nova Scotia to Florida. Like the alewife, blueback herring are anadromous and both of these river herring are keystone species and are vital to the aquatic ecosystem. Predators such as ospreys, herons, striped bass and seals rely on blueback herring to survive and without this fish, the food chain would be severely disrupted.

American Shad – Alosa sapidissima: The American shad is native to the east coast of the United States and Canada and are anadromous. A Federal Trust fish, the American shad is protected under the United States Anadromous Fish Conservation Act. This legislation supports the improvement and revitalization of fish habitat through conservation and research efforts. Known for its edibility, the American shad’s populations, like the river herring, have been negatively affected by dams and other forms of human impact.

Historic Site: No

Park: Yes

Beach: No

Boat Launch: Yes

Lifeguards: No

Size: 34 acres

Hours: Dawn to Dusk

Parking: Limited on-site parking at 418 West Elm Street.

Cost: Free

Trail Difficulty: Easy

Facilities:

Picnic tables, benches and interpretive signage. Fish ladder. Geocache location.

Dogs: Dogs must remain on leash. Please clean up after your pet!

Boat Ramp: No

ADA Access: No

Scenic Views: Yes

Waterbody/Watershed: Indian Head River (North River watershed)