The First Decade

By Jim Glinski, Scituate

Even though the NSRWA lacked a permanent office and held meetings in private homes, under the leadership of its first president, Bill Finn, it got right to work to preserve the scenic and recreational values of the North and South Rivers. In January it published its first newsletter, edited by Nick and Jeanne Mills. As reported in the newsletter, the first open meeting of the NSRWA was held on October 27, 1970 and was attended by a “capacity audience” to hear Mr. Alan Morgan of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, who expressed great enthusiasm and pledged his support for the organization. Since the meeting membership had swelled to over 200 concerned citizens from the 12 watershed towns. The newsletter also reported on the actions the Watershed had taken in the first months of its existence. These included halting illegal dredging in the Humarock marshland, blocking an open sewage pipe in First Herring Brook in Scituate, requesting tests of Scituate’s water supply in reaction to reports of possible night-soil contamination, assisting the newspaper recycling project in Scituate, and temporarily halting the illegal filling of wetlands behind Sinnott’s Garage in Marshfield.

Even though the NSRWA lacked a permanent office and held meetings in private homes, under the leadership of its first president, Bill Finn, it got right to work to preserve the scenic and recreational values of the North and South Rivers. In January it published its first newsletter, edited by Nick and Jeanne Mills. As reported in the newsletter, the first open meeting of the NSRWA was held on October 27, 1970 and was attended by a “capacity audience” to hear Mr. Alan Morgan of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, who expressed great enthusiasm and pledged his support for the organization. Since the meeting membership had swelled to over 200 concerned citizens from the 12 watershed towns. The newsletter also reported on the actions the Watershed had taken in the first months of its existence. These included halting illegal dredging in the Humarock marshland, blocking an open sewage pipe in First Herring Brook in Scituate, requesting tests of Scituate’s water supply in reaction to reports of possible night-soil contamination, assisting the newspaper recycling project in Scituate, and temporarily halting the illegal filling of wetlands behind Sinnott’s Garage in Marshfield.

One practical problem confronting the Watershed was a need for a central headquarters to keep its files and from which it could disseminate information about environmental issues. This need was temporarily met by Mr. and Mrs. Charles Lamb who donated office space on Highland Street in Marshfield, which would be manned by volunteers. However, it would not be until May 1974 that space was acquired on Route 3A in Marshfield for the organization’s headquarters.

Another issue facing any new organization is to create an organizational structure. At the first annual meeting of the NSRWA on October 13, 1971 at Central School in Norwell, the first order of business was to elect a new slate of officers. This was, in part, necessitated by the resignation of President Bill Finn, who was going back to college to earn a degree in environmental planning at Harvard, although he would remain active in the Watershed as chairman of its Technical Advisory Committee. Bill would be succeeded as president by Carl Smith, with Jean Foley elected vice-president, Elizabeth Burbank, treasurer, and Beverly Guild as secretary. In the summer of 1972, Mr. Alan Bates, a member of the Watershed ‘s Board of Directors, designed a new organizational structure which attempted “to streamline the various functions of the Association, to more clearly define and delineate the role of each committee and to prevent duplication or overlapping of effort.” In January 1973, a new set of officers was elected with James Guild becoming the Association’s new president, Reed Stewart the new vice-president, Lois Graham, the new secretary, and Elizabeth Burbank continuing as treasurer. In 1974, a new set of by-laws was created, which reduced the workload of the president and created a greater separation of policy making and administrative functions.

While getting its organizational act together, the Watershed continued with its core mission of protecting the waters of the North and South Rivers. It produced a slide show, “A Threat to the North and South Rivers,” which it would show to civic organizations, libraries, and schools and continued its monitoring of the Scituate Sewage Treatment Plant and the town’s Stockbridge Dump, which was the source of night soil run-off into the First Herring Brook Watershed. The Watershed’s Land Acquisition Committee, chaired by Dr. Carl Pipes, investigated the possible acquisition of Trouant’s and Bartlett’s Islands at the junction of the North and South Rivers, which were both for sale and being eyed by developers. The Watershed lacked sufficient funds to purchase the two islands, but it hoped to raise money from the Nature Conservancy, the Massachusetts Audubon Society, the Trustees of Reservations and/or the Ford Foundation. Although it commissioned an in-depth study of the islands by a group of Harvard Graduate students, the Watershed was unable to secure the funding to buy the islands. This resulted in newly installed president Jim Guild informing members in the first newsletter of 1973 that, “Bartlett’s Island has been bulldozed” and “Trouant’s Island will have a long bridge running 2,000 feet along the North River marshes.” However, at the end of the year he was able to announce that the Watershed had received a grant from IBM which enabled it, under the direction of vice-president Reed Steward, and with the assistance of Paul Blackford, to create a land-use map of the entire watershed.

In addition, the Watershed had joined a lawsuit by Norwell citizens against the Hanover Mall, which was accused of filling in wetlands and altering the course of Third Herring Brook without a permit. The lawsuit was successfully concluded by a consent decree with the owners of the Mall agreeing to maintain an adequate parking lot drainage system and a series of retention dams in the relocated Third Herring Brook and to end any further relocation of the brook. In the fall of 1974, the NSRWA launched its River Preservation Project, which had as its objective the long-range protection of the North and South Rivers through state and federal legislation, conservation restrictions, and citizen action. This project led the organization to begin work on two of its most important accomplishments of the 1970s.

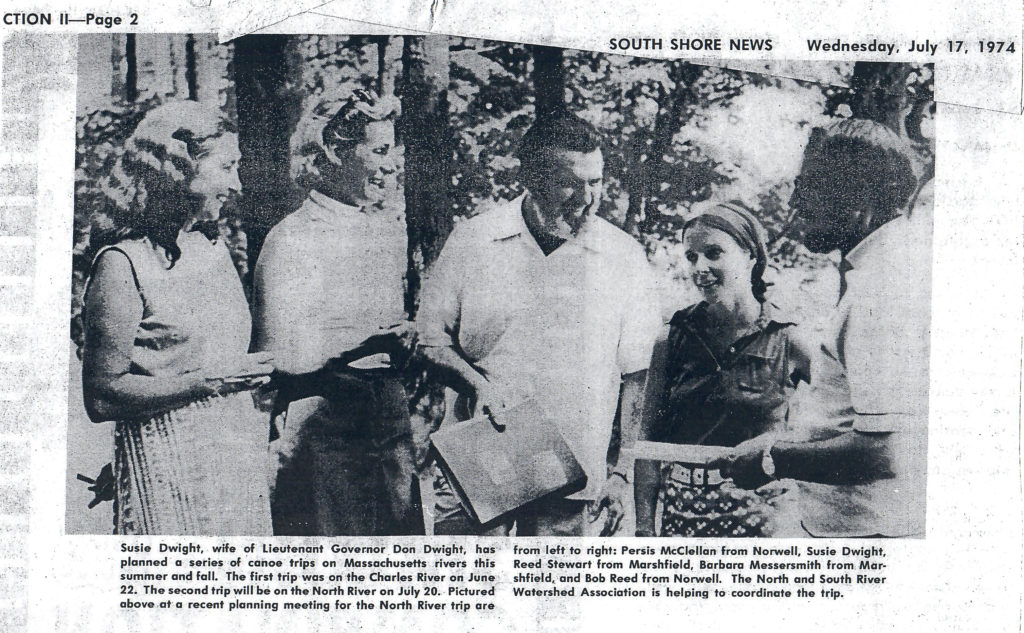

At this time, the NSRWA began work on its goal to obtain a Scenic Protective Order for the North River, under that state’s Scenic Rivers Act of 1971. The goal of the Protective Order was to maintain the scenic quality of the North River Basin and to promote recreational use of the river while allowing property owners to reasonably develop their property. The campaign received a big boost from the publicity generated by a July 1974 canoe trip on the North River planned by the Watershed in cooperation with Susie Dwight, wife of Lieutenant Governor Donald Dwight. One hundred and two canoes and more than 300 persons participated in the trip, along with numerous spectators, calling attention to the recreational value of the river and promoting the Watershed’s Scenic Protective Order proposal. However, as a March 1997 article in The Christian Science Monitor noted, “no single individual did more to prod the state” to designate the North River as a scenic river than Jean Foley. Jean, along with Watershed Association president Reed Stewart, marshaled local forces and sent a 500-signature petition to the state. In addition, she wrote up an environmental and historical assessment of the river, which was submitted to Betty Wood, then commissioner of the state Department of Environmental Management (DEM). Jean and her husband, Jack Foley, also held brunches and cocktail parties to bring environmentalists and developers together in support of the project. In 1978, as a result of these efforts, the North River became the first scenic protected river in Massachusetts.

At this time, the NSRWA began work on its goal to obtain a Scenic Protective Order for the North River, under that state’s Scenic Rivers Act of 1971. The goal of the Protective Order was to maintain the scenic quality of the North River Basin and to promote recreational use of the river while allowing property owners to reasonably develop their property. The campaign received a big boost from the publicity generated by a July 1974 canoe trip on the North River planned by the Watershed in cooperation with Susie Dwight, wife of Lieutenant Governor Donald Dwight. One hundred and two canoes and more than 300 persons participated in the trip, along with numerous spectators, calling attention to the recreational value of the river and promoting the Watershed’s Scenic Protective Order proposal. However, as a March 1997 article in The Christian Science Monitor noted, “no single individual did more to prod the state” to designate the North River as a scenic river than Jean Foley. Jean, along with Watershed Association president Reed Stewart, marshaled local forces and sent a 500-signature petition to the state. In addition, she wrote up an environmental and historical assessment of the river, which was submitted to Betty Wood, then commissioner of the state Department of Environmental Management (DEM). Jean and her husband, Jack Foley, also held brunches and cocktail parties to bring environmentalists and developers together in support of the project. In 1978, as a result of these efforts, the North River became the first scenic protected river in Massachusetts.

The Protective Order would regulate the land 300 feet on both sides of the North River, essentially extending Massachusetts Bay in-land through Scituate, Marshfield, Norwell, Hanover, Pembroke and Hanson. The Order would be administered by the newly created North River Commission, which was comprised of one representative and one alternate from each of the six-member towns and had the authority to regulate such actions as development and vegetative cutting within the 300-foot corridor of the river’s natural banks. The North River Commission would be funded by an annual grant from the state Department of Conservation and Recreation to the NSRWA as the administrative agency, which would in turn fund the North River Commission. The overall result of the Protective Order was that the North River looks pretty much today as it did in 1978.

The Protective Order would regulate the land 300 feet on both sides of the North River, essentially extending Massachusetts Bay in-land through Scituate, Marshfield, Norwell, Hanover, Pembroke and Hanson. The Order would be administered by the newly created North River Commission, which was comprised of one representative and one alternate from each of the six-member towns and had the authority to regulate such actions as development and vegetative cutting within the 300-foot corridor of the river’s natural banks. The North River Commission would be funded by an annual grant from the state Department of Conservation and Recreation to the NSRWA as the administrative agency, which would in turn fund the North River Commission. The overall result of the Protective Order was that the North River looks pretty much today as it did in 1978.

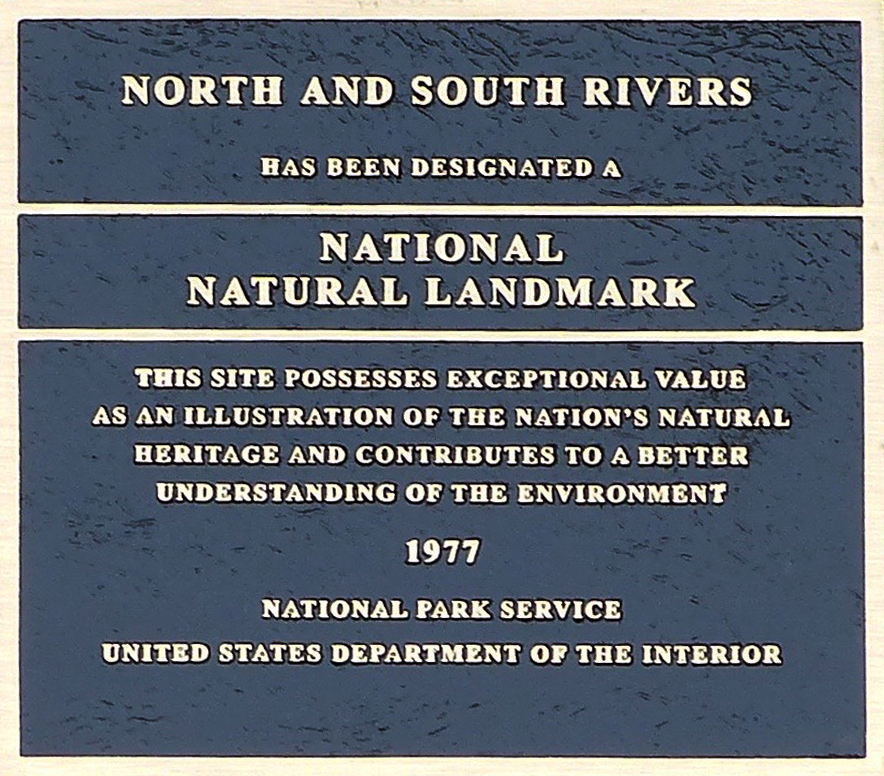

In 1977, the Watershed accomplished its second major goal of the 1970s, when it got the North and South Rivers designated as a National Natural Landmark by the federal government’s Department of the Interior. The stated goals of this program were “to encourage the preservation of sites illustrating the geological and ecological character of the United States, to enhance the scientific and educational value of the sites thus preserved, to strengthen public appreciation of natural history and to foster a greater concern for the conservation of the nation’s natural history.” These goals made the Department of the Interior and the NSRWA complementary partners in preserving the North and South Rivers watershed.

In 1977, the Watershed accomplished its second major goal of the 1970s, when it got the North and South Rivers designated as a National Natural Landmark by the federal government’s Department of the Interior. The stated goals of this program were “to encourage the preservation of sites illustrating the geological and ecological character of the United States, to enhance the scientific and educational value of the sites thus preserved, to strengthen public appreciation of natural history and to foster a greater concern for the conservation of the nation’s natural history.” These goals made the Department of the Interior and the NSRWA complementary partners in preserving the North and South Rivers watershed.

With the North River Commission in place to oversee the regulations of the Protective Order, in 1978 the NSRWA made the decision to play a decreasing role in local environmental issues, ending the first phase of its history. While it would continue to act as a watchdog over private and municipal developments, such as the maintenance of the causeway to Trouant’s Island and the continuing problems with the Scituate Sewage Treatment Plan, it would not be actively engaged in local environmental issues until the organization’s regeneration in 1985.