Early Activism Leads to Cleaner Rivers

By Jim Glinski, Scituate

By Jim Glinski, Scituate

The Scituate Wastewater Treatment Plant was built in the 1960s to treat town sewage and to discharge wastewater into the ground only. Over time the sand filtration system became inadequate to treat the growing volume of sewage. During the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, unbeknownst to the public, this resulted in the discharge via a pipe of millions of gallons of partially treated sewage into the Herring River, a tributary to the North River. During the 1980s testing showed that the pollution of the North and South Rivers was increasing, and it caused the shellfish flats to be closed indefinitely to recreational harvest. Not surprisingly, one potential source of the pollution was identified as being a location along the Driftway in Scituate; the location of the Wastewater Treatment Plant.

The opening salvo in its battle with the Scituate Wastewater Treatment Plant came in 1986 when the NSRWA announced that the plant was documented to have discharged over 100,000 gallons of wastewater (purportedly, partially treated) into the Herring River on August 5 and August 6. This discharge only became public knowledge due to the efforts of whistleblowers who notified local papers. At this time the NSRWA announced that it would launch “a methodical investigation” into the operation of the plant, including the frequencies of its discharges and would insist on the upgrading of the plant to prevent further degradation of the water quality. In order to implement this policy the NSRWA’s Board of Directors set up the Scituate Treatment Plant Monitoring Committee (STPMC) which would make the public aware of the plant’s untreated or partially treated wastewater discharges every time they occurred and notify the state Department of Environmental Quality Engineering (DEQE) and the local media of the event.

In April 1987, the NSRWA succeeded in pressuring the DEQE to issue Administration Order 698, which imposed a moratorium on all new sewer connections to the Treatment Plant. The DEQE also ordered the Town of Scituate to develop a facilities plan to come up with alternative measures for treating its sewage. In the spring of 1989, the issue heated up as a result of Scituate’s request to lift the sewage hook up moratorium in order to allow a developer to build 100 housing units at Cushing Hill with no on-site septic system. At the time NSRWA Board President Damon Reed made it clear to the Scituate Board of Selectmen that the NSRWA was strongly opposed to lifting the moratorium and that it was prepared to “either work with or against the Town of Scituate, depending on their resolution, to maintain the moratorium.” On May 23, the Board of Selectman, by a vote of 3 to 2, upheld the moratorium.

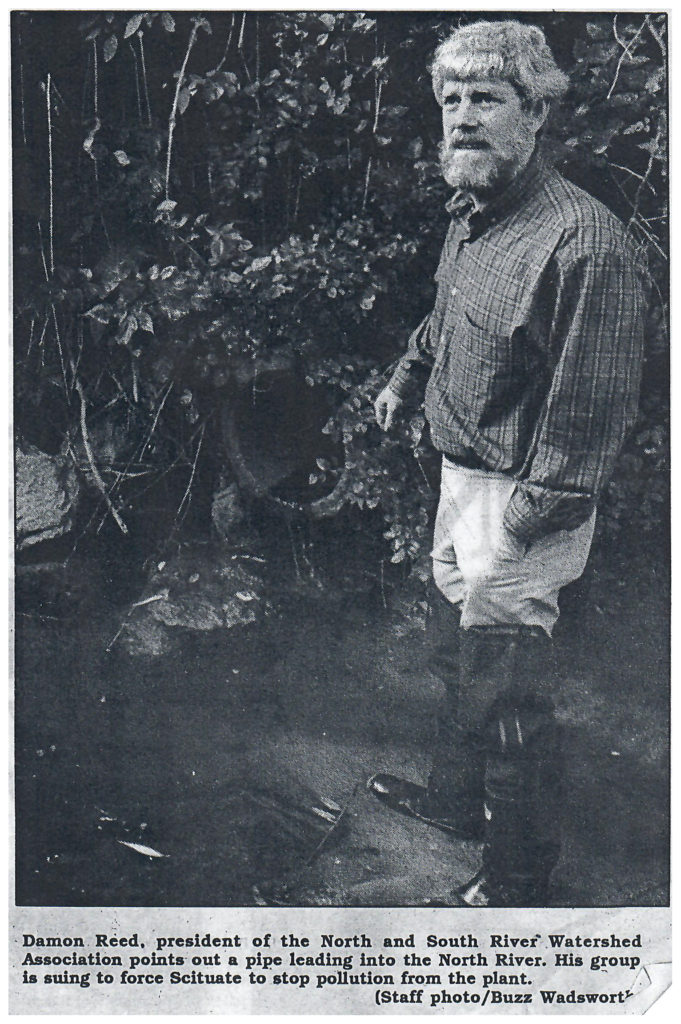

Unfortunately, despite the 1987 consent order, the pollution caused by the plant continued. In June 1989, the NSRWA announced a seven-point “Plug the Pipe campaign.” The campaign urged residents of all the towns along the river to sign a petition, to place “Plug the Pipe” bumper stickers on their cars, and to support legal action against the Town of Scituate. In the summer of 1989, the Association announced its plan to file a suit against the Town of Scituate to force it to stop pollution from the plant. In August the NSRWA received a phone call from someone, referred to as “Deep Throat”, with knowledge about a discharge valve at the plant and its location. Accompanied by a reporter from a local paper, Gary Thomas and Damon Reed, visited the location and found the discharge pipe. The following day a picture appeared in local papers of Damon Reed pointing out the “mystery pipe” which was discharging sewage into the Herring River. Finally, in October 1989, the NSRWA took the major step of filing a $71 million lawsuit against the Town of Scituate, a total determined by counting the number of days since the plant’s pollution had been identified and multiplying that number by the $25,000 a day fine for violating the Federal Clean Waters Act. The suit charged that the town was violating the Federal Clean Waters Act by discharging raw and partially treated sewage into the Herring River.

Unfortunately, despite the 1987 consent order, the pollution caused by the plant continued. In June 1989, the NSRWA announced a seven-point “Plug the Pipe campaign.” The campaign urged residents of all the towns along the river to sign a petition, to place “Plug the Pipe” bumper stickers on their cars, and to support legal action against the Town of Scituate. In the summer of 1989, the Association announced its plan to file a suit against the Town of Scituate to force it to stop pollution from the plant. In August the NSRWA received a phone call from someone, referred to as “Deep Throat”, with knowledge about a discharge valve at the plant and its location. Accompanied by a reporter from a local paper, Gary Thomas and Damon Reed, visited the location and found the discharge pipe. The following day a picture appeared in local papers of Damon Reed pointing out the “mystery pipe” which was discharging sewage into the Herring River. Finally, in October 1989, the NSRWA took the major step of filing a $71 million lawsuit against the Town of Scituate, a total determined by counting the number of days since the plant’s pollution had been identified and multiplying that number by the $25,000 a day fine for violating the Federal Clean Waters Act. The suit charged that the town was violating the Federal Clean Waters Act by discharging raw and partially treated sewage into the Herring River.

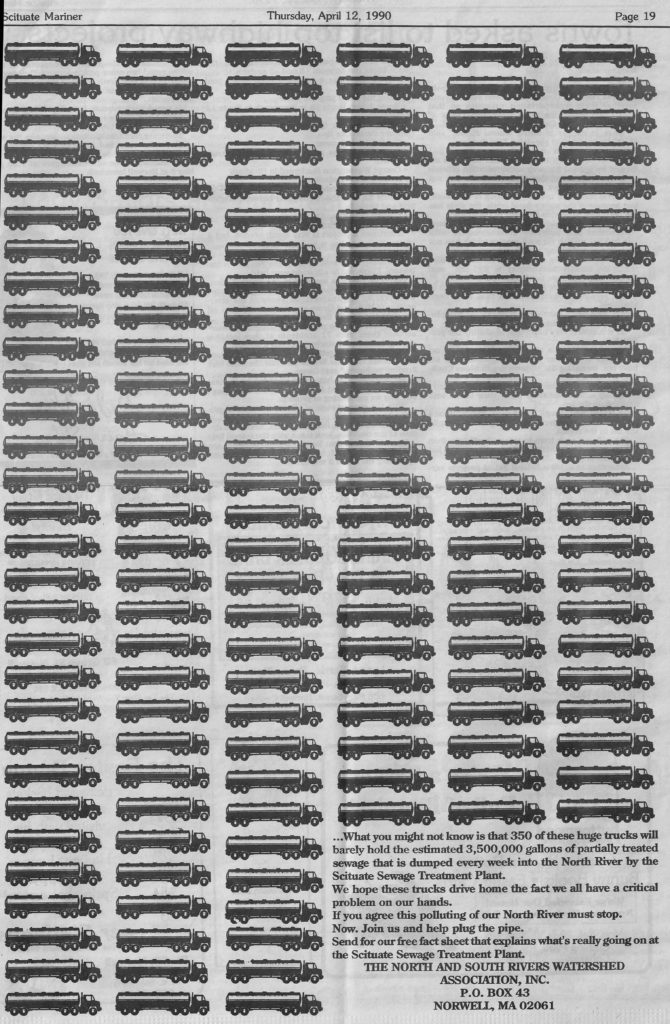

The suit and the continued use of the media to highlight the Plant’s continued pollution of Herring River increased tensions between the NSRWA and the Town. One example of this was the accusation by Scituate’s Town Counsel John Giorgio that NSRWA president Damon Reed and Gary Thomas, the NSRWA’s lawyer in the suit, were making “misleading and libelous statements” and “grandstanding “ to the press. At one point he threatened to bring Gary Thomas up on charges in front of the state Board of Overseers, because he had violated state law by trying the case in the press, making it impossible for the Town to receive a fair trial. Copies of the letter sent to the NSRWA by Giorgio were also sent to Town officials, left anonymously in the mailbox of The Patriot Ledger at Quincy town hall and mailed to the newspaper’s office. One month later the NSRWA placed two full-page ads filled with images of over three hundred fifty 10,000 gallon tank trucks, representing the 3,500,000 gallons of partially treated sewage dumped into the North River by the Scituate Sewage Treatment Plant every week.

The suit and the continued use of the media to highlight the Plant’s continued pollution of Herring River increased tensions between the NSRWA and the Town. One example of this was the accusation by Scituate’s Town Counsel John Giorgio that NSRWA president Damon Reed and Gary Thomas, the NSRWA’s lawyer in the suit, were making “misleading and libelous statements” and “grandstanding “ to the press. At one point he threatened to bring Gary Thomas up on charges in front of the state Board of Overseers, because he had violated state law by trying the case in the press, making it impossible for the Town to receive a fair trial. Copies of the letter sent to the NSRWA by Giorgio were also sent to Town officials, left anonymously in the mailbox of The Patriot Ledger at Quincy town hall and mailed to the newspaper’s office. One month later the NSRWA placed two full-page ads filled with images of over three hundred fifty 10,000 gallon tank trucks, representing the 3,500,000 gallons of partially treated sewage dumped into the North River by the Scituate Sewage Treatment Plant every week.

The NSRWA received a setback when, in January 1991, its suit against Scituate was dismissed by U.S. District Court Judge Joseph L. Tauro on the basis that the suit was asking the federal government to do what the state Department of Environmental Protection was already doing: asking Scituate to fix its treatment plant. This decision supported the Town’s contention that it was doing everything possible to come into compliance with new EPA wastewater standards. However, the U.S. Department of Justice sent EPA lawyer Catherine Flanagan to argue, in support of the NSRWA’s suit, for an appeal of Judge Tauro’s decision. Flanagan, along with NSRWA lawyer Gary Thomas, argued that while the state ordered the Town to find a solution to the sewage discharge, it did not require Scituate to pay a penalty, nor did it tie the Town to a cleanup schedule, thereby validating the NSRWA’s suit. However, in December a federal appeals court upheld Judge Tauro’s decision, concurring with the Town’s argument that the suit constituted double jeopardy. Although the NSRWA considered taking its case to the U.S. Supreme Court, on April 13, 1992, the fifth anniversary of the sewer moratorium, it announced it was dropping its lawsuit, because, as Executive Director Dan Jones said, “ it just doesn’t seem to be going anywhere.”

After a couple of years of attempting to get six local, state, and federal agencies on the same page, a second Administrative Order of Consent was issued in December 1994. This AOC established a timeline which stipulated what Scituate was required to do to bring its Wastewater Plant into compliance with all applicable state and federal laws and regulations. As a result, Scituate was ordered to install advanced nitrogen removal devices, create an infiltration and inflow reduction plan, prepare an environmental impact plan, and provide funding for these projects. The order would require the new sewage treatment plant to be completed by June 1999 at an estimated cost of $10 to $13 million.

In August 1994, after years of being bitter adversaries, representatives of the Town and the NSRWA met to discuss how they could cooperate to confront the serious pollution problems facing the North River. In an article in The Patriot Ledger, entitled, “Concern for North River unites former adversaries,”recently appointed NSRWA Executive Director Debbie Lenahan, stated that, although the Association would prefer not to have treated sewage running in the river, we know that the Scituate Sewage Treatment Plan is not the only major source of pollution on the river. At the same time, Town Administrator Richard Agnew stated that “Scituate wanted to do everything it could to assure the water quality of the river is as clean as it can be, but we don’t want it to be all at our expense.” This change in attitude by both sides allowed the NSRWA and the Town to share information and work together to solve problems facing the North and South Rivers watershed.

In August 1996, the Town of Scituate received grants of $647,000 to plan upgrades to the Sewage Treatment Plant, which included doubling the capacity of the plant and upgrading the treatment process to discharge effluent which would approach drinking water quality. At town meeting in March 1997, Scituate voters approved a $15,117,000 appropriation for the treatment plant upgrade. The plant upgrade was completed in 2000, along with the construction of stormwater improvement structures to protect and improve the water quality of the North River and estuary.

Today, the plant regularly discharges clean effluent and allows the NSRWA to sample the effluent through the RiverWatch water quality monitoring program. While the plant still has challenges with infiltration and inflow (clean groundwater seeping into the pipes) particularly during storm events the relationship between the town and the NSRWA is now one of cooperative partnership. The NSRWA remains committed to partnering with communities to address our collective water challenges – to ensure clean and adequate water for both people and nature.