Lately I’ve become fascinated with a certain stretch of the Indian Head River. From the bridge on Cross and State Streets, at the Hanover-Hanson town line, to Luddam’s Ford Park in Hanover and Pembroke, the river flows for two miles through a peaceful, secluded valley. On the Hanover side, a wide, mostly-flat woodland trail traces the route of the historic Hanover Branch railroad, passing behind private homes as it follows the course of the river. On the Hanson and Pembroke side, a network of cart paths and narrow trails provides access to both the forested upland and the water’s edge. It takes about two hours to walk the complete circuit.

Within this stretch lies an area once known as Project Dale. In Barry’s 1853 Historical Sketch of the Town of Hanover, it is described as, “very pleasant, . . . surrounded by hills, clothed with evergreen, and deciduous trees.” A dale is a valley – usually a broad, open one. Today, this part of the Indian Head is no longer broad nor open, but it remains a valley . . . a geographic feature that’s relatively rare in our watershed.

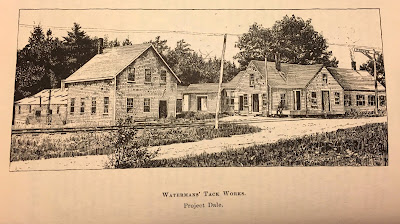

But what – you might ask — is does the word “Project” signify? It’s hard to imagine, since now it’s so serene, but just 150 years ago this was a booming center of industry. “Project” likely refers to enterprise – specifically the tack factory that stood here. Between the tack factory, the railroad, the nearby anchor forge and additional factories, this was a busy place.

|

| (from Briggs’ History of Shipbuilding on North River) |

Back in those days, the water level in the river was significantly higher and wider. Not for any natural reason – but because of dams. There was a dam at the tack factory, and when you walk along the water’s edge on the Hanson side of the river, you can easily discern where the water used to flow.

There was – and still is – a dam at Luddam’s Ford too. While dams may fuel industries, they also prevent migratory fish from reaching their spawning grounds. These days, with the factories on our rivers long since gone, many communities are opting to remove obsolete dams and restore fish passage.

Project Dale is a captivating spot. One of the best ways to access it is through the Tucker Preserve, a property owned by the Wildlands Trust. I recommend starting from the Pembroke side of Luddam’s Ford Park on West Elm Street, where you’ll find a large parking lot. Look upstream across the pondside meadow, and you’ll see a kiosk with a trail heading into the woods.

For now, pay no attention to the colorful graffiti-covered ruins on the wooded side of the trail. We’ll get back to those later. Instead, keep your eyes on the river. Follow the path along the water’s edge. Soon a wooden bridge leads you across a brook, and then the trail begins a moderate incline.

There is a wider, flatter option to the left, but the narrow trail to the right offers the best view. This is the Indian Head River, appearing more like a pond here because of the dam downstream.

The trail continues through the woods to a second stream crossing, and this time you’ll have to make your way across flat rocks to reach the other side. Some days, it’s easy. Other days, when more water is flowing, the crossing requires precise footwork.

At this point you will have entered a hemlock grove. If you look toward the river, you’ll find that you’ve climbed to the top of a ridge. Very likely you’ll spy a building in the distance. Continue along the trail, deeper into the woods. As the trail veers closer to the edge of the ridge, look down again. The valley is much narrower here, and incredibly picturesque. You are now at Project Dale. The building across the river was once the Waterman Tack Factory.

Beginning in the 1700s, this site was home to a number of industries. The earliest was probably a carding mill, where wool fibers were prepared for spinning. Other incarnations included a fulling mill (to clean and thicken wool fiber), and later a grist mill. In 1830, a tack factory moved in. Several owners later, it became the domain of L. C. Waterman & Co. In 1860, with 12 machines in operation, it employed 8-10 people and produced to 50-60 tons of tacks per year. Waterman tacks were used primarily in shoes, but also in the furniture and upholstery trades, and for laying carpet. Historians indicate that many shoe repair shops, even in New York and Philadelphia, would only use Waterman tacks. The business continued to expand and thrive, and by 1875 it employed 25 people and produced 250 tons of tacks per year.

I love this spot for its beauty, but even more because of how it illustrates the passage of time. Looking down from the ridge, you can see scattered remains of a concrete dam along the water’s edge.Scanning the course of the river, you might imagine how the power of the water behind the dam was harnessed to fuel the factory. You can probably guess where the water went in, and where it went out. But now, 150 years later, where has it all gone?

In February 1886 there was an unusually heavy rain – what historians refer to as a “freshet.” The water rose at such speed, and to such height, that it severely damaged not only the factory but the adjacent train tracks. The railroad was repaired, but ceased operations in the 1930s. Subsequent storms in 1938 and 1954 did permanent damage to industries throughout the river valley. Since then, Project Dale has become a different world. It’s so quiet now – and so natural — it’s hard to imagine it was ever any other way.

The trail continues a short distance from the factory overlook and soon reaches the Tucker Preserve’s western boundary.

Turn back here, and retrace your route until you reach the brook you crossed on foot. This time, proceed to your right and follow a loop trail through the southern half of the 78-acre property. (I recommend carrying a map). This will eventually bring you back to the wooden bridge and Luddam’s Ford.

As you approach the end of the trail, you will once again notice brightly-graffiti’d ruins in the woods off to your right.

These are remains of the E. H. Clapp Rubber Works, which stood on both sides of the river at the turn of the 20thcentury. Norwell native Eugene Clapp began his enterprise in Hanover in 1873, using water power to grind and process rubber. By 1879 he was using steam power, and soon expanded into multiple buildings on both the northern and southern banks.

A decade later, according to Briggs’ History of Shipbuilding on North River, he was “doing two or three times as much work as any of his competitors, and (was) handling more than one half of this business in the United States.”

|

| from Briggs’ History of Shipbuilding on North River |

Thanks to the Wildlands Trust, the Tucker Preserve has been open to the public since 1993. It’s a special place — not only rich in history, but populated by unusual (for this region) vegetation and wildlife. It is open daily from dawn to dusk.

by Kezia Bacon

March 2019

Kezia Bacon’s articles appear courtesy of the North and South Rivers Watershed Association, a local non-profit organization devoted to protecting our waters. For membership information and a copy of their latest newsletter, contact NSRWA at (781) 659-8168 or visit www.nsrwa.org. To browse 20 years of nature columns, visit http://keziabaconbernstein.blogspot.com